The Year I Learned to Stop: What a Sabbatical Taught Me About Being Enough

by Silvia Paz

The phone rang the evening before. I was in transition from a closed session meeting, already on the dais, I felt my iPhone vibrate and I stole a glance to see who was calling. On my screen the words: Latino Community Foundation. I wondered why they would be calling after hours, so I made a mental note to return the call. But they called again the next morning. “We wanted to talk to you before Thanksgiving,’ two excited voices took turns in telling me, ‘because in recognition of all you do to improve your communities you have been selected to be part of our ‘Rest is Power’ initiative.” A paid sabbatical program. The invitation was simple: commit to a three-month sabbatical, completely disconnected from work – zero contact. Would I take it?

I had determined I needed to be exceptional since I was a kid. The pressure to succeed started early, amplified by the responsibility I carried. As an elementary school student, I learned English as a second language, primarily so I could act as a translator for my mother at crucial appointments – at the DMV, social security offices, and doctor’s clinics. I was responsible for ensuring that a language barrier didn’t result in a costly mistake. A weight far too heavy for a child, that also yielded rewards: I became good at delivering what others required of me.

By the time I was in high school it was a known fact: Silvia was the model student. I remember being told that several of my teachers were debating the mandated writing model – a structured, five-paragraph essay format that every student was required to use. Some teachers argued that the structure was too rigid and formulaic, producing technically correct, yet robotic essays. Arguing in support of the model, my English teacher pointed to my essays as a good example, to which my history teacher responded, “Well of course,” throwing his arms to the air, his long beard revealed a tight smile, “that’s Silvia.” Suggesting that my skill was not due to the model, but was powerful enough to succeed in spite of it.

And that became me – someone who was going to succeed in spite of my circumstances. I was going to jump through every hoop necessary, be lucky enough to find people who saw my potential, not be discouraged by the times I came to an empty mobile home, to an empty fridge, to spend another day in extreme temperatures. Seeing education as the only escape route, I became a straight A student, delivering the valedictory address with a full-ride scholarship in hand to a prestigious private university.

The fundamental problem was that I didn’t learn how to stop. To say yes to a sabbatical I needed to accept hard truths.

The possibility of slowing down didn’t just feel uncomfortable; it registered as a profound existential risk. Consequently, I always did the opposite: I accelerated.

This tendency wasn’t a recent development; it was a deeply internalized survival mechanism. I recall my college years, where the university required a student to enroll in 12 units per semester to be considered full-time. I consistently took 16. This was never a casual ambition, a pursuit of academic status, or a desire to prove my intelligence to others. It was a compulsion – a learned behavior where my security, and my future felt conditional on my performance.

Stopping meant confronting the unspoken fear of what I might lose or what I have already lost. But I had to do this. I have heard that the signs of burnout are many, but they are clear – for me an early manifestation came in the form of a deep craving for solitude. So I said yes to a life I had never really known.

I traded in my professional calendar for a different kind of schedule: traveling to my daughters’ softball tournaments, spending hours sun-drenched and cheering our girls All-Stars team with a singular focus – not worried about zoom calls, not rushing to make it to the next meeting, and certainly not tethered to my phone.

This freedom extended to simple, profound human connection. I made time for people, not for a quick coffee-and-agenda, but truly talking our hearts out without the pressure of time. And I was home-making: I found joy in washing dishes, clearing the counters, and vacuuming floors. This to my husband’s surprise who reassures me he didn’t marry me for my homemaking talent. These seemingly mundane tasks were anything but; they provided moments for me to reconcile with God.

Sitting on a bench one day, I read the calling to “Be still” as written in Psalm 46:10. It was a calling the way God calls those who are in need of rest. No, this didn’t look like a day at the spa. It was a wrestling match against feelings of hurt, guilt, and shame. “Be still and know.” I know God held me through pain and struggles. But on this day I had to surrender that part of my identity. My existential crisis was no more. “Be still and know that I am God.” The Lord’s assurance, “I am,” became the foundation upon which I could finally rest.

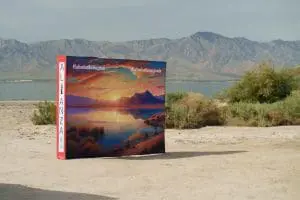

Today I can still feel the moments of lightness I experienced during my sabbatical journey: feeling my soul stretch in the shape of a smile in the presence of the desert mountains against a blue sky. I relish in the memories of my children, becoming their own complex beings. I know I can step away without the world falling apart, and that it is possible to live a life of purpose with a more calm spirit.